It happens all the time. An elected official says, “That social services office has a budget of $1 million, but we have other offices. Let’s ease our budget woes by closing that office and saving $1 million.”

Not so fast!

That claim makes the following unspoken assumptions:

- That the office’s work is of no value and

- That there’s no downside to closing the office.

Both assumptions are almost certainly false. Let’s imagine why.

Photo Credit: FraserElliot via Compfight cc

Suppose it’s a Health and Human Services office in a county-seat town that manages many public social services. After it’s closed, people in the area have to travel farther to an office in a larger town.

Now those that were working to overcome poverty, unemployment, homelessness, family problems, mental health issues, addictions, domestic violence, and so on face more hassle. Some won’t go to the new office or won’t go as often as before because they don’t have transportation, can’t afford the higher fuel costs, or don’t have time due to work and family pressures. That means they don’t get the help they need, and they and their communities suffer.

When budget-cutters say we can’t afford it, I think they mean they aren’t convinced that it’s important. So the remedy is to make not only a fiscal case in support of the office/program/service but also a moral case.

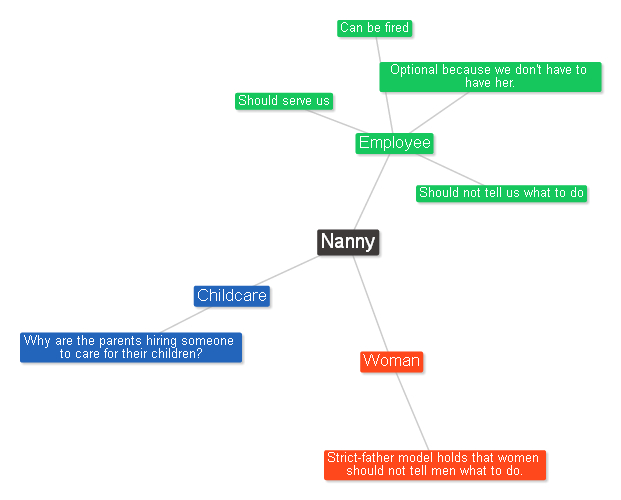

The moral case would be grounded in what George Lakoff calls (in Thinking Points, Chapter 4, pp. 53-54) progressive morality:

- Empathy. If you needed what that office offered, how would you want to be treated?

- Responsibility to act upon empathy, not just to feel it.

- Protection of vulnerable citizens from harm.

- Expansion of freedom by increasing, not reducing, access to needed services

- Fulfillment (as in “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness”)

- Opportunity. Reduced access to services means opportunity is lost.

- Fairness and equality. With the office closed, would social services be available on a fair basis?

- Human dignity. Every American has a right to live in dignity.

At their best, social services support the common good by expressing all these values.

So when the budget-cutters brag about how much they’ll save us by cutting, Framologists could respond like this (if true in the specific case):

“Mr. Budget Cutter says he’ll save us money. But his plan would cost us access to help in distress, loss of the freedom and dignity that come from solving our problems with a little help from the community, reduced opportunity to enjoy ‘life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness,’ and more unequal access to public services. That seems like a pretty high price. And then there are the likely financial costs of his plan….”

Pretty powerful, huh? Is it laying it on too thick? How do you argue for protecting what you value from the budget ax?